from https://www.insidehighered.com

Big Proctor

Is the fight against cheating during remote instruction worth enlisting third-party student surveillance platforms?

Chief among faculty and student concerns are student privacy and increasing test anxiety via a sense of being surveilled. Pedagogically, some experts also argue that the whole premise of asking students to recall information under pressure without access to their course materials is flawed. This, they say, may only motivate students to game the system, when cheating is what online proctoring services seek to prevent.

Of course, concerns about academic dishonesty are what gave rise to online exam proctoring in the first place. And the switch to rapid remote instruction provides new opportunities and motivations to cheat: everyone is away from campus, under considerable stress.

New Stresses, New Temptations

The past few weeks alone have seen two public cheating scandals. Georgia Institute of Technology said that it is investigating allegations that students who took a physics final over the analytics-focused platform Gradescope sought help through Chegg, a subscription-based tutoring website, during the 24-hour period the test was available. Boston University also said that it is investigating alleged cheating through Chegg, including on open-book quizzes in chemistry. In both cases, the university is working with Chegg to determine which students sought the illicit help.

Cases like these can tip the pro-con scales in favor of online proctoring for some professors. It’s possible that these examples may have been prevented by certain proctoring programs that lock down students’ computers to prevent them from toggling away from their assessments. They may also have been flagged in real time by programs whose remote proctors or algorithms monitor students over webcams for suspicious behavior.

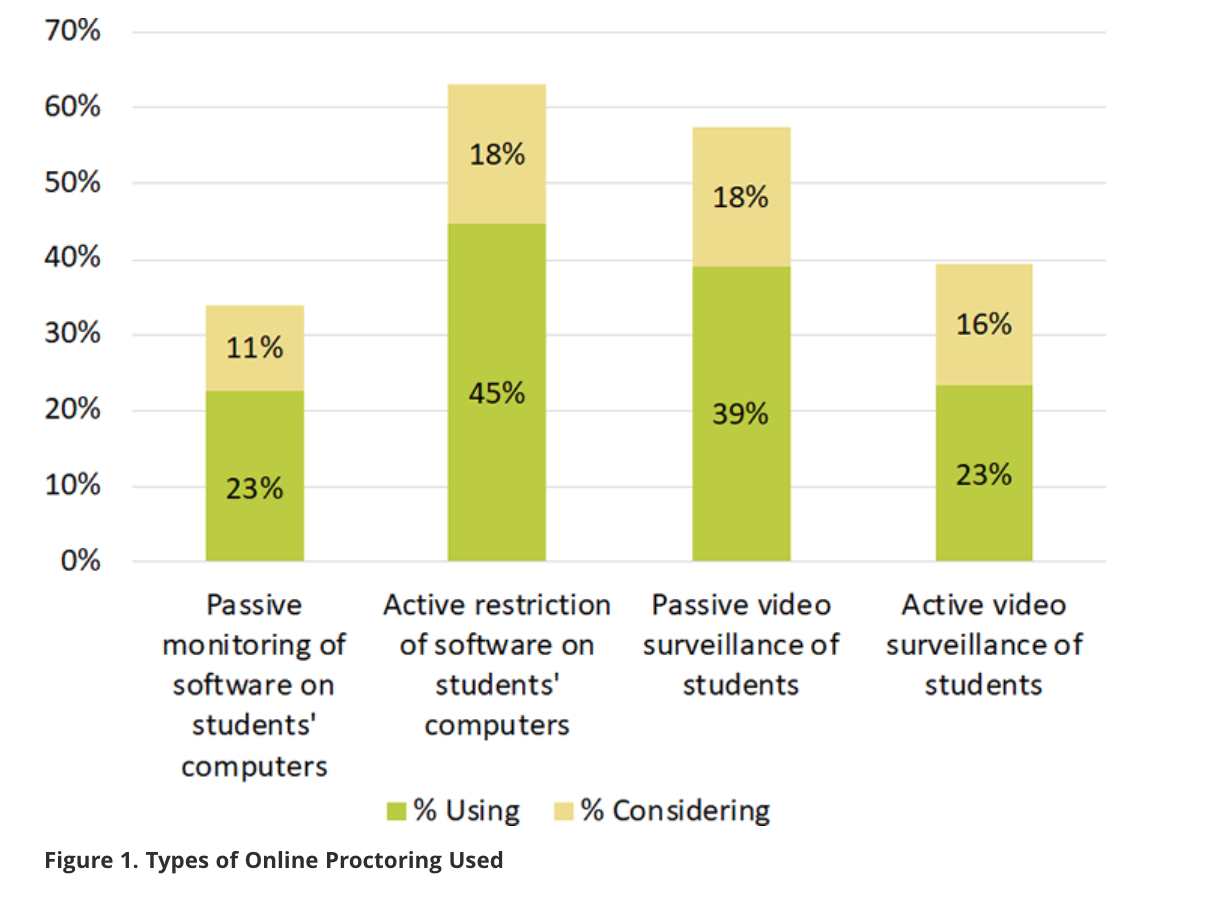

According to an April Educause poll, 54 percent of institutions were using online or remote proctoring services, while another 23 percent were considering or planning to use them. Even so, over half of the institutions polled said they were concerned about cost, as well as student privacy. Twenty-six percent of institutions said they were using products that didn’t meet their accessibility standards. Respondus was by far the most widely used product. The most popular method of surveillance was active restriction of students’ computers, but most institutions use more than one form.

Source: Educause

Source: Educause

A recent study published in the Journal of the National College Testing Association involving undergraduate engineering students suggested that students would be more likely to cheat in an unproctored environment than a proctored one. The authors concluded that it’s “imperative to establish a culture and expectation in higher education around the purpose of testing and assessment that incorporates the impact of academic dishonesty.” Such efforts also need to address the “perception of higher education today as transactional in nature and of the need to get good grades as more important than the acquisition of knowledge.”

A Level Playing Field

Sarah Whorley, assistant professor of biology at Daemen College in New York, uses LockDown Browser and Respondus Monitor by Respondus, which are available to her through her campus. The product training session pitch that resonated with her was “keeping everyone on a level playing field.”

That said, Whorley took students’ concerns into account in various ways: before going “all in,” she polled students about their technology access at home, took screenshots of herself going through the Respondus monitoring process to demonstrate what test behaviors might get flagged and prompt a review by her, and showed them what a final video would look like to help them feel less self-conscious. Indeed, most proctoring programs record students’ test sessions for a given number of days or months, but individual professors are only prompted to review these sessions when something appears out of the ordinary.

She’s had no major problems yet in either her lower- or upper-division courses. Some freshmen have complained, however, that some of their peers were subjected to monitoring while other were allowed to take open-book tests.

“We dealt with that complaint by explaining that each instructor was testing according to what they thought was best,” and by reminding students that many had selected their professors based on personal preference, she said. One other minor issue: a facial movement function that beeps when students look away proved distracting in her biostatistics class, as students needed to frequently look down to work out problems on scratch paper.

“I can just turn off that feature next time,” though, Whorley said.

However flexible these programs can be, many professors still reject them as a form of surveillance.

What Is Cheating?

Andrew Robinson, instructor of physics at Carleton University in Canada, said he’s heard about cheating via Chegg, but he tried to make it “very difficult” during his recent open-book final exam, which accounts for 30 percent of students’ grades. He has large courses — up to 400 students each — but still managed to give every student a different test by creating a deep question bank with randomized variables in calculations.

On cheating, Robinson said, “You can either implement surveillance tech to prevent that, which will inevitably be bypassed eventually, or come up with different assessments.” And even without the final exam, he added, “other course elements assess competence just fine.” Other assessments include five smaller closed-book tests, online assignments and participation scores from clicker use.

Jesse Stommel, senior lecturer in digital studies at the University of Mary Washington and co-founder of the Digital Pedagogy Lab, said “cheating is a pedagogical issue, not a technological one. There are no easy solutions.”

The work doesn’t begin “with an app or a license for a remote proctoring tool,” he said. Instead, teachers have to start by talking “openly to students about when and how learning happens,” so they take ownership of their educations.

“We have to start by trusting students and using approaches that rely on intrinsic motivation, not policies, surveillance and suspicion.” Everyone wants this pivot to all-online instruction to work, Stommel added, and anxieties about testing are high. But maintaining “the status quo isn’t possible and so-called solutions like remote proctoring tools will create many more problems than they solve.”

Tom Haymes, a consultant at IdeaSpaces design lab, said we’re “not framing the question the right way.” Instead of asking why “traditional” exams aren’t working online, he said, “we need to be asking what exactly it is that we are trying to achieve with them.”

The shift to remote instruction has shown the “cracks in this mode of thinking,” Haymes continued, in that if the “game” is to take a test, “the focus often turns to how you beat the test. It’s rarely about learning anymore because most tests do such a poor job of measuring actual, deep learning.”

The result? An “arms war between the student using technology to defeat the game and the teacher trying to use technology to defeat the student’s attempt to defeat the test.”

Haymes argued for assessments that force students to “use the knowledge in some meaningful way,” that ask them use information the way they do in “real life.”

Creating an “actual product,” he said, “is much harder to cheat on.”

‘Creepy AF’

The Ph.D. Story, a popular Twitter account run by an anonymous Los Angeles-area adjunct professor, polled followers last month on whether they’d use the online proctoring program her institution was offering, which monitors students’ exam behavior via webcam and microphone. The survey was obviously unscientific but informative nonetheless. Of more than 1,000 respondents, 81 percent said no.

“Now is not the time. Read the room. Many students are hurting,” wrote one professor. “Creepy AF and would totally slaughter me if I had test anxiety,” wrote another follower.

Some worried that students with disabilities, such as those who practice self-stimulatory behavior or “stimming,” may get flagged again and again for suspicious behavior, or have to disclose sensitive medical information to avoid this. Others worried programs that ask students to scan their environment for contraband materials before they take a test — typically by circling the room with a laptop to the satisfaction of the remote proctor — may feel shame or discomfort about showing their living conditions to a stranger.

In the COVID-19 era, it’s also very possible that tests may be interrupted by children, siblings, parents or other family members (even pets). To that point, some professors argued that it’s unethical to impose online proctoring on students midway through a semester, during a crisis, if they hadn’t agreed to it at the beginning of a course.

Many respondents to the poll advocated open-book testing and questioned whether traditional testing really demonstrates student learning. “IMO, the most important thing is if the students learn the material,” said one professor. “At the end of the day I don’t really care if they learn it from me or by competent use of Google.”

Similarly unscientific but informative is a scan of social media for students’ experiences with online proctoring. These comments mostly fall into two categories: complaints and questions about how to outsmart the programs and cheat anyway.

Students’ Rights

Concerns outweigh comments about cheating. Complaints range from awkward (a student reported that his professor had contacted him to request that he stop cursing out loud so much during exams so as to appear less suspicious to the proctoring program) to emotional (many report the format heightens their test anxiety) to technical. On the technical side, students cited unsuitable test time slots due to remote proctor availability (one said he had to take a test at 11 p.m.), long wait times for proctors to answer questions before starting exams, incompatibility between personal computers and platforms, and bad internet connections during exams. In most cases, students are only allowed to log in to a test once, so getting booted offline mid-exam is a big deal.

Students voice privacy concerns, as well. They want to know what data is being collected, by whom and for how long. Some programs have responded by publishing a list of student rights. ProctorU is among them. In March, however, the company took criticism from the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, among other groups, for sending a cease-and-desist letter to faculty members at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who opposed the program in a letter to their chancellor.

Citing overall student privacy concerns and those of undocumented students in particular, the campus’s Faculty Association Board wrote, “We recognize that in our collective race to adapt our coursework and delivery in good faith, there are trade-offs and unfortunate aspects of the migration online that we must accept. This is not one of them.”

Ashley Norris, chief academic officer at ProctorU, said the matter had since been resolved amicably. She also noted that ProctorU drafted a Student Bill of Rights for Remote and Digital Work to start a conversation around online testing. Among other rights, the document says students can expect to have their questions answered, be presumed to be honest and accurate, and be served by entities that are compliant with laws and regulations related to student privacy and student data. They also have the right to a review, the right to understand why specific and limited data are collected and whether they’re shared.

Norris, an educational psychologist and former dean at the University of Phoenix, said that while some students report higher test anxiety with online proctoring, others prefer scheduling tests around their schedules in their own, familiar surroundings. Mass testing centers are becoming less common as even regularly administered licensing, certification and accreditation-based exams are employing programs such as ProctorU, she said. And while these services are not necessarily appropriate for every context, they are necessary and appropriate.

ProctorU’s business has picked up significantly in the last few months, with most of the extra usage coming from prior institutional partners now dealing with offering online tests at scale, Norris said. This has meant more staff and faculty training, including on student rights.

“On data and privacy, we’re very clear that we don’t own or control the data,” nor do the company’s data subprocessors. “We never sell or share it with third parties, and we’re trying to make that as clear as possible.”

Integrity and Growth

Scott Foote, chief information security officer at Examity, an online proctoring company, said growth is up 35 percent from what was expected this fiscal quarter. The company has struggled somewhat to keep pace in hiring, vetting and training new proctors in this remote environment; the company’s Slack troubleshooting chat channel is busier than usual. Faculty and proctor training is nonnegotiable for the company, however, he said, as they need to know what they’re looking for and what they aren’t.

“There’s always something that happens — a dog barking or a kid coming into the room,” he said. “But if I’m taking my exam and turning my hand over and over again looking into my palm, that’s an easy tell.” Both proctors and automated programs know to ignore everyday behaviors such as thinking out loud or eye rolling.

Asked how often students cheat, Foote said he didn’t know. Institutions always make the final decision on who has been dishonest after a review of footage and don’t typically report their findings back to the company.

Examity also needs to be sure there’s no collusion between students and proctors, which is harder to control in a remote context instead of the secured environment in which proctors typically work. On student privacy, Foote said that the most sensitive data students typically share is the government ID with which they verify their identities. Examity protects this and other data in accordance with international privacy laws and employs Tier 1 data centers to process them.

Bill Fitzgerald, a privacy researcher at Consumer Reports, said no online proctoring company stands out above the rest as having a stellar privacy record.

Instead of blaming online proctoring companies entirely, Fitzgerald said that institutions need to come up with better assessments for students that don’t lend themselves to or encourage cheating. There are open-note tests, portfolio assessments, take-home exams and video-based assignments to start, he said, even for big courses.

“The structural inequities of the education system can’t keep flowing down onto students. If somebody’s saying it’s taking too much time to make a good assessment, that’s not the students’ problem,” he said. “When the evaluation is predicated on the idea that the student is going to cheat and they’re going to be surveilled into compliance, that’s just not an acceptable starting point.”

Amelia Vance, director of youth and education privacy at the Future of Privacy Forum, said she’s especially troubled by any program that accesses students’ browser histories, beyond the scope of what’s necessary to ensure the integrity of the test. The collection of sensitive medical information and treatment of students with disabilities are additional worries.

Vance said that students’ preferences should be part of the ongoing debate over online proctoring, as some students prefer live human proctors while others prefer AI technology, for example.

“A lot of this is about what students feel comfortable with,” she said, “going back to the fact that the answer might be no monitoring at all.”